Virtual world helps solve real plumbing issues

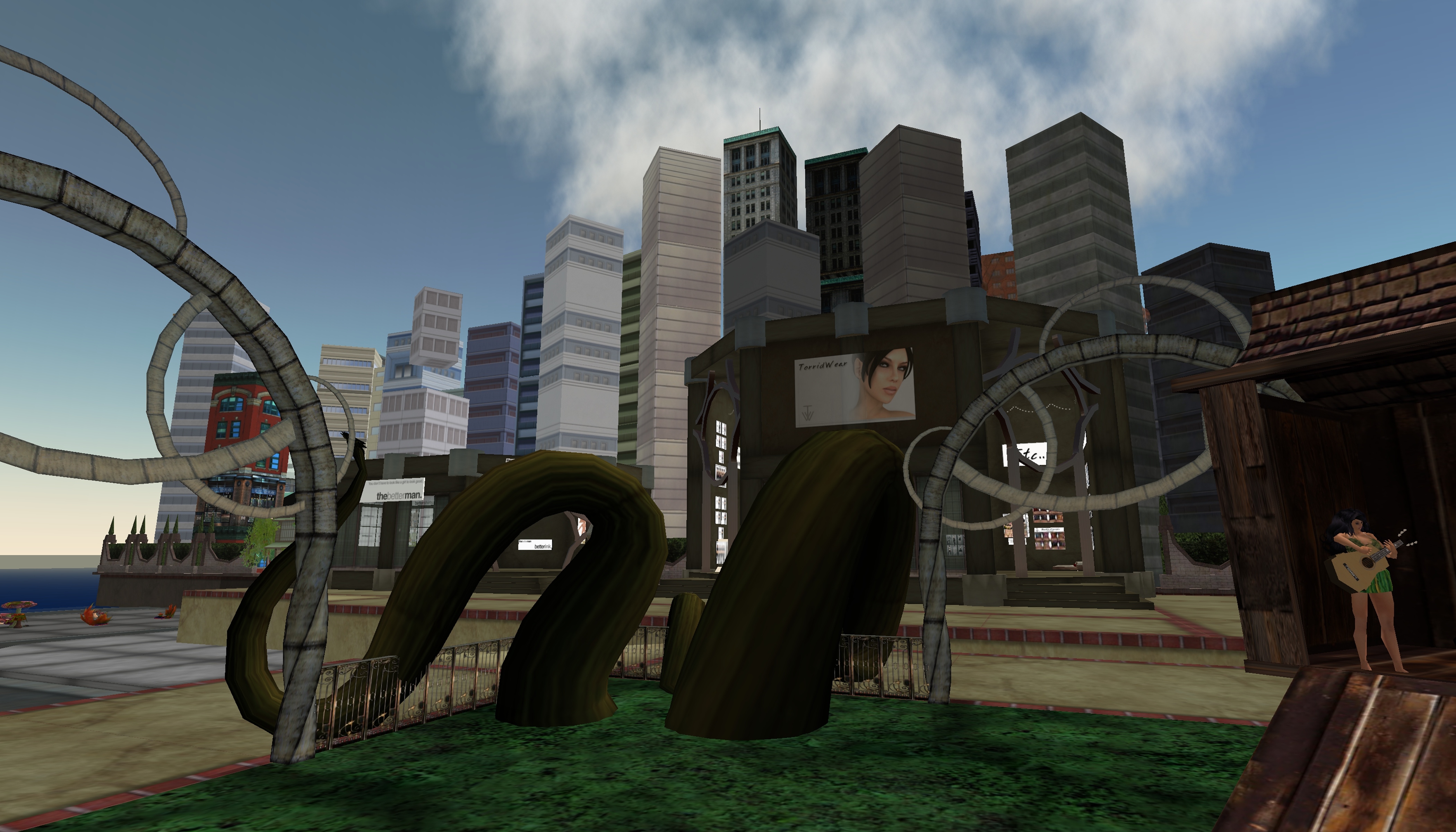

In 2003 the world was introduced to Second Life (SL) – an online, virtual world where ‘players’ could become whomever they wanted to be. But, as the technology used in digital gaming developed, and through the addition of a free service for basic users, people started to find new ways of using the virtual world to make money in the real one.

In its original format, SL was intended to be just another online multi-player experience designed by Linden Labs in San Francisco. But SL now has more than nine million members, several of whom use the technological platform to operate or extend their real-life businesses.

The online community even has its own legal currency called the Linden. The exchange rate between the two worlds sits between 250 and 320 Linden dollars to one United States dollar.

Pam Broviak, who goes by the online alias of Pam Renoir, is the public works director and city engineer for La Salle, Illinois, in the US.

Broviak now uses her SL alter ego to help in designing new plumbing systems for her clients. She has also initiated the Second Life Public Works Resource Center – one of the first destinations in the so-called ‘metaverse’ focused on applying SL to real-world engineering.

“Right now it’s hard to make money in SL because it’s so new – the real-life business community is just starting to discover it,” Broviak says.

“I only got involved in SL to explore different ways to use it for engineering, because I believe it has a lot of capabilities and tools. I also wanted to try creating a worldwide community of engineers that can meet and talk about engineering.”

Membership in the public works community gives you access to a new monthly magazine about engineering in the virtual world, SLEngineer.

Broviak says she first heard about the program at an Autodesk University – an annual conference put on by the manufacturers of AutoCAD.

“An architect gave a demonstration of it. I thought ‘wow, I can use that’, so I got involved and I’ve been with it ever since, just trying to find different ways of using it for work.

“It was ideal, because I don’t have a lot of time to travel, but I still like to know what’s going on in the industry.

“I work for a city, so I started using the program by designing a new plumbing system to show the residents how we could reconfigure their basements to prevent sewage back-up. It was so much easier to build in SL then print it out to show them than to draw it in CAD.”

Broviak has created three online groups: civil engineering, construction and public works. There are about 40 members in both the civil engineering and constructions groups, and 20 in the public works group.

“The problem I have found is that people who aren’t used to SL are just not sure about it because it looks like a game. But I suppose it’s a learning process, and it’s going to take some time for people to get used to the system.”

Starting off small, Broviak purchased a parcel of ‘land’ for just US$5 a month. Since then, she has expanded by buying a whole ‘island’ for the members of her public works and engineering groups.

The island cost almost US$1,700 to buy and will cost a further US$295 each month to maintain.

“There are a few other engineering groups in SL, but we all tend to congregate on my island and have meetings.”

Broviak says one of the biggest differences between SL and its competitors is that it is free to download and access. Users can join to explore, meet people, go to classes or build temporary items without paying membership fees.

Building objects in SL involves using a series of primitive 3D geometric ‘prims’. Objects can contain between one and 255 prims, which are mainly boxes, cylinders, prisms, spheres or rings.

Unlike most 3D software, SL uses parametric modeling to reduce the amount of data traveling between your computer and the SL server, which increases the speed at which the program operates.

Broviak says one of the best features of using SL is that you don’t need a strong background in CAD to create realistic and interactive products in the online world.

“If you draw something with CAD, everything is just sitting on the computer. It’s hard because you aren’t there interacting with it: you can’t touch it and you can’t move around it.

“Sure you can look at it, but in SL you have a ‘person’ there, so you can see the size in comparison to you, walk around it, sit down to get the perspective from your sitting position, see how it looks, see how the landscaping or flowers look and see different colors. It’s much more realistic and it’s much more interactive.”

Broviak can’t wait until the day she can go into SL when she wants to buy a pump or a valve, enter a virtual store and talk to a supplier, see all of the products and how they fit into her design right then and there. Even if the supplier is halfway across the country.

“The big thing it’s going to do is help with communication and collaboration in these groups. Engineers can meet there to discuss engineering or a design in real time.

“It’s a really good tool for collaborative work on designs, and I think it’s a really good tool for the public. If you have a design you want public input on, you can build it there. People can visit it, leave comments and make suggestions.

“It’s definitely going to connect people a lot more, potentially across the whole world.”