Simple filtration and design fixes that make rainwater safer

As safe rainwater harvesting becomes increasingly vital due to climate change and Australia’s growing population, our plumbing industry’s challenge is to make continual improvements to rainwater collection and storage systems. Philip Doust writes.

In the 2022 Summer edition of Plumbing Connection, an article by Ken Sutherland, a Hydraulic Consultant, claimed that there was “confusion” with our plumbing codes (AS/NZS 3500.3) as standards had “fallen between the cracks,” as detailed by Ken with an “inverted siphon” for a rainwater catchment strategy that places considerable pressure on stormwater lines, as specified in Kens charged pipe design of his article.

Ken maintained that “the cracks come in” as his “charged design” required water pipes standards of AS/NZS 3500.1, allowing for the water pressure, which is contrary to low-pressure stormwater pipe standards of AS/NZS 3500.3. I was somewhat perplexed at what I considered a colossal amount of misinformation about these plumbing standards. Therefore, as a Master Plumber who completed a five-year apprenticeship in the 1960s, with another two years to become a licenced plumber (PL304) in Western Australia, I offer my views based on my experience as a licensed plumber and inventor of plumbing products.

Firstly, our plumbing codes came about to protect and serve the health and safety of the community in overcoming deadly waterborne diseases like typhoid. In the early years of Australia, and typically of this era in WA, a typhoid epidemic claimed up to 20% of (mostly) healthy young men. In fact, in the 1890s, nearly 2,000 people in WA were officially recorded as dying of the disease, though many considered the actual number was far more significant.

Thus, our health and not hydraulic mathematics became the catalyst for our current plumbing codes, which I believe hold “no awkward questions,” as Ken claims in his article. Our plumbing codes developed as families grieved the loss of their loved ones. The Australia of the twentieth century urgently required competent plumbing to ensure the health and prosperity of our communities. And while it is not widely appreciated, to solve this problem, plumbers got together. They formulated our bylaws with drainage, water supply, fixture rates and detailed the all-important physical break between drinking and wastewater.

Correctly, the Master Plumbers Association of Western Australia has an excellent publication, In Good Hands, which documents the incredible achievements of the founding fathers of our plumbing codes. But unfortunately, these ‘Good Hands’ did such an excellent job with our bylaws or, as we now call them, plumbing codes that nearly everyone takes our plumbing industry for granted. Given this understandable apathy, I believe the general community has come to the view that plumbing is, in essence, simple. Or, as Ken considers it, a calculation in pressure and flow rates.

So, what’s the fuss with Ken’s rainwater catchment design? After all, numerous rainwater tank installers opt for the “inverted siphon” or, as they say, the “wet system.”

Inverted siphons

I doubt that if the rainwater systems’ design and installation remained under licensed plumbers’ control, we would have seen these types of “inverted siphon” installations. Licensed plumbers are well aware of the term “disconnector trap” (DT), and its purpose as a “disconnector trap” with a water seal is to protect a dwelling from a sewer overflow and odour. Yet, strangely the “disconnector trap” has been adapted in rainwater installations and rechristened as an “inverted siphon”.

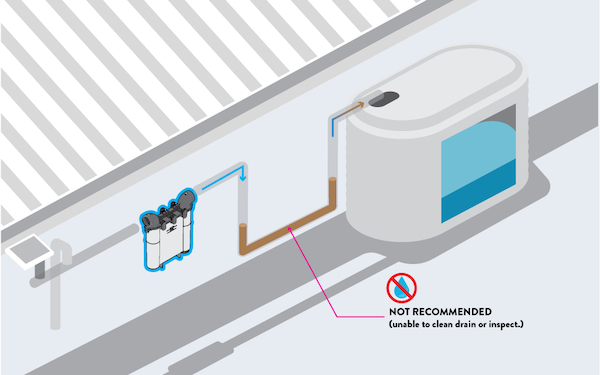

Could it be because the “inverted siphon design” is more pleasing to the eye, and as Ken states, it works as we even have one under the Brisbane River. After all, you can keep the rainwater tank often out of sight. Apart from the aesthetics, I am concerned with the “health” of the rainwater and the maintenance costs with these “inverted siphons” or “running traps”, which have previously only been used in soil lines. In soil lines with the decomposing matter, it matters little. However, condensed decaying matter in a rainwater line that you may wish to drink is not good.

Ken appears to party address this issue in Figure 1 of his design with an “inspection chamber at the lowest point.” However, this begs the question: If the homeowner wanted to inspect and clean his rainwater line with Ken’s design, he would be flooded while finding it extremely difficult to clean. Therefore, in my view, this is not a practical design. It is no accident that graded (no ponding) plumbing soil lines require inspection points at every 90° change of direction. Apart from these maintenance difficulties, we have the smell of decomposing material trapped in the “inverted siphon”, which has to compromise the “health” of the stagnant rainwater, which surely makes the rainwater more costly with increased filter replacements. In addition, water tank sterilisation chemicals are often required to make the rainwater “healthy” to drink.

Rainwater quality

So why should collecting and storing rainwater now be considered such an issue? As recently reported in a story by ABC News’ Romy Stephens, rainwater tanks can host potentially deadly bacteria. In Romy’s story, Mr Tim O’Halloran, the homeowner, remarked: “You put your rainwater into a little cup, leave it there for an hour or two, then you watch the water turn a horrible, horrible colour, and you know it’s full of some sort of germs.” Mr O’Halloran’s observations are exactly as we found rainwater in Thailand when we conducted a rainwater test in conjunction with Associate Professor Thunylux Ratpukdai PhD of the Department of Environment and Engineering at Khon Kaen University.

Curiously, there was a time when nearly everyone had a rainwater tank and drank rainwater, so let us turn back the clock to the 1950s, as I grew up drinking rainwater, and no one got sick. The rainwater tank we had was fitted with a waterpipe straight to our kitchen sink, and if the water got a bit smelly, my mum would always despatch me to look inside the tank.

I usually found a dead frog, which I removed, and off we went drinking the rainwater. Whatever pollution there was in the 1950s, a glass of rainwater and the rainwater tank always remained crystal clean.

Pollution

In 2015 I contacted the Centre for Water Research at the University of Western Australia. I discussed these rainwater quality issues with celebrated Professor Jorg Imberger, who heads up the Environment Engineering Department. Suffice to say it was challenging to find the exact cause of this pollution, other than motor vehicles, which again provided no insight into how the harmful bacteria came about in our rainwater.

Rainwater today

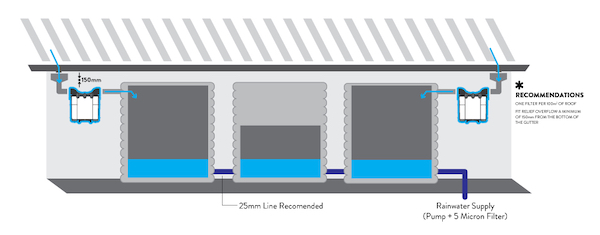

In my view, rainwater still has to be the best available, and with a properly designed rainwater catchment system, there is nothing like rainwater to drink. The bonus is that we could significantly reduce our mains water consumption with only 2–3 cubic metres of rainwater storage per household. However, in my view, the “inverted siphon” installation holds a dearth view of what is required for collecting and storing rainwater; therefore, it is inconsistent with our plumbing codes. At the same time, even with existing “inverted siphon” installations, technologies exist, such as pre-tank filtration with a RainWatch Filter, reverse osmoses units and UV sterilisation if the rainwater is required as drinking water. After all, all our water was once rainwater, so why not catch it before it soaks into the ground?

The RainWatch Filter is designed to purify water in an easily accessible manner.

Pre-rainwater tank filtration

I appreciate I have a vested interest in the following. However, my interest in rainwater catchment and storage came about as follows. In 1998 I invented a new tap washer which I named the DoustValve, which has gone on to achieve sales in the millions. Thus, I left my plumbing contracting business and became a manufacturer of my products. At the same time, I have always loved rainwater and how great it was for washing clothes, as it’s highly soft water that makes your clothes clean and soft.

Unfortunately for me, living in Sorrento, a northern suburb close to Perth, WA, my rainwater tanks, pump filters and washing machines became blocked by contaminants that resembled a black paste-type material.

Nevertheless, as I had the manufacturing and design capabilities, we decided to solve the problem, which we did with the RainWatch Filter, as shown installed with a “Dry System” for rainwater catchment.

RainWatch Filters are installed in Africa, Vietnam, Thailand and many rural areas of Australia. They have stopped everything from cane toads to small insects decaying in rainwater tanks. While some RainWatch Filters work hard, others with the 50-micron 316 stainless filter lightly polish the rainwater while protecting the rainwater from vermin in the summer months. Given the documented contamination concerns since the 1950s, I believe it is only a matter of time before pre-tank water filtration with filters such as the RainWatch Filter becomes the best practice in our plumbing codes.

Understandably, for the reasons I have given, it is self-evident that our plumbing codes, by omission, do not consider “inverted siphons” to have any place in rainwater lines other than wastewater lines, no mix and match, and neither are they required if we follow the best health practices with the catchment and storage of rainwater.

Please find more detailed information on our rainwater design and catchment, including details about our RainWatch Filter.

Philip Doust is managing director of Doust Plumbing Products, WA.