Toilet to tap technology

Tongji University in Shanghai is one of China’s premier engineering campuses. Its College of Environmental Science and Engineering educates tomorrow’s environmental engineers from around China, as well as teaching English-based studies to visiting international students, particularly from a variety of African countries.

The University also hosts the Tongji-German Institute, a joint initiative of the Chinese and German governments to facilitate cultural exchange and cooperative initiatives between academics from the two countries.

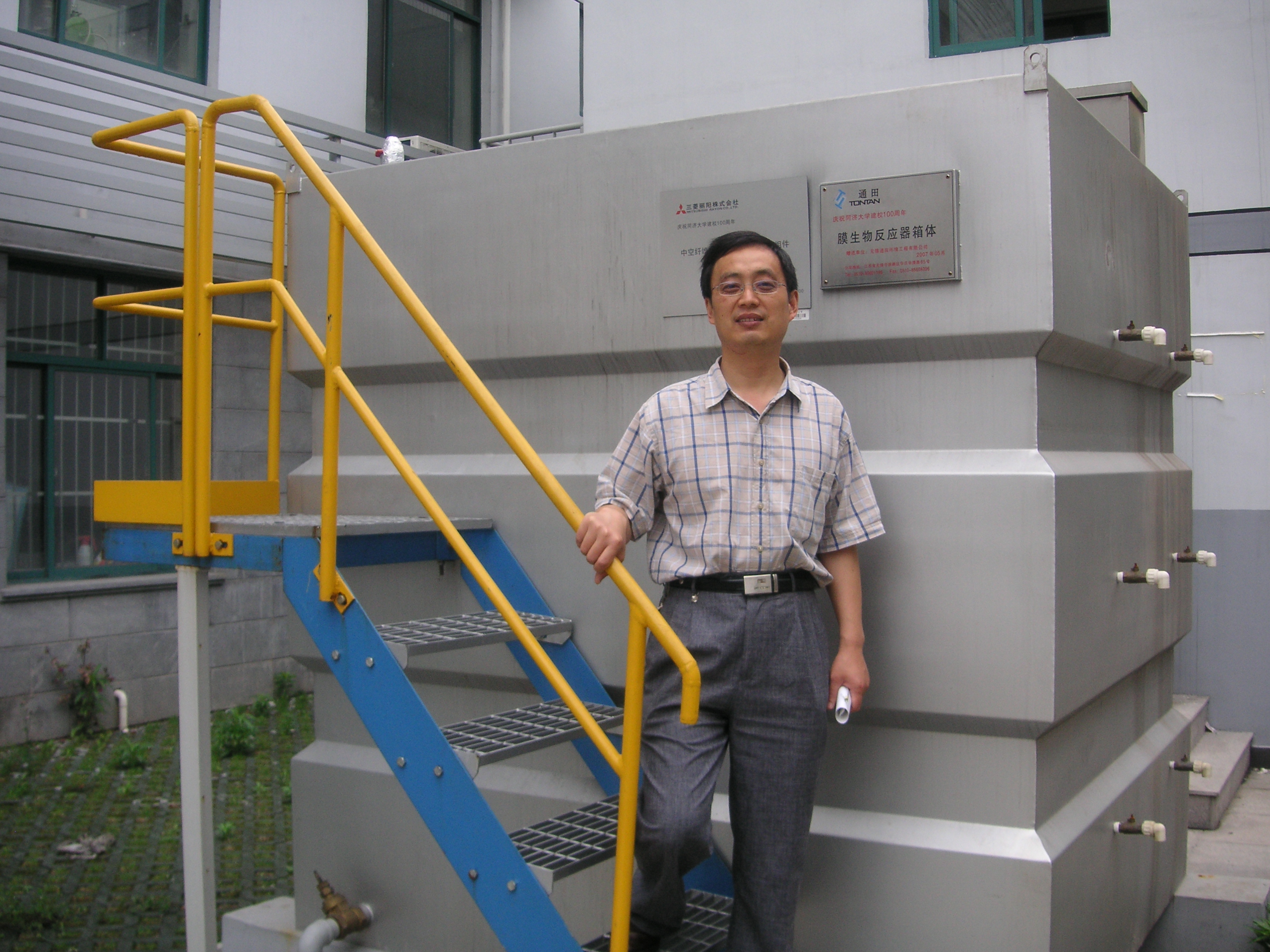

With its large number of students (approximately 15,000), the university’s own facilities provide an excellent opportunity to develop and test new technologies in a controlled situation. Environmental engineering Professor Siqing Xia, Vice Dean of the College of Environmental Science and Engineering, leads a number of project teams at the campus who are aiming to solve some of China’s growing and acute water problems.

With more than 1.3 billion people and 175 cities in China housing over a million people each, the need for decentralized solutions is going to be a major requirement.

If engineering solutions can be found to reuse grey and black water rather than lose it to drainage, there is a great opportunity to reduce the consumption of primary potable water. The problem is a huge negative public response to the idea of direct potable reuse (also dubbed ‘toilet to tap’ technology or water reclamation) which greets this sort of solution – both in China and elsewhere around the globe.

Professor Xia predicts that 2010 will be the year China embraces ‘toilet-to-tap’ water treatment technology. He plans to conduct another demonstration for the Shanghai World Expo in that year, and expects more interest and acceptance of the technology by then. In the meantime, he strives to educate the public about the technology’s benefits through an important demonstration project at the University.

Prof Xia has created a small scale toilet-to-tap treatment plant on the Tongji University campus. The plant turns wastewater from the College of Environmental Science and Engineering’s lab into pure potable water. This water is used for a number of purposes around the campus, including scientific procedures and irrigation of the surrounding landscape.

The Professor says the water is so clean it can be used for carbon-chip washing or kidney dialysis, but the so-called ‘yuck factor’ means students and the general public are reluctant to try it, and the water from the Tongji project does not end up in drinking glasses, despite its purity. Direct consumption of water that has been through the sewerage system is frowned upon, and the issue is not confined to China; it is a universal problem which has water companies and governments looking to share experiences in turning public opinion around.

But Professor Xia is optimistic that by 2010 toilet-to-tap technology will be widely accepted and the interest in direct potable reuse technologies will propel this technology forward.

Testing at the university sees wastewater from laboratory building toilets and rainwater collected in tanks on campus and funneled into a membrane bioreactor, which uses membrane technology and traditional biological treatment with bacteria to remove nutrients. Pollen, colloids, silt, bacteria, protozoa cysts and large viruses are then filtered out by the membrane component.

Much of the water dispensed from the membrane bioreactor is then disinfected and reused as greywater in the lab-building toilets or for landscaping. Left over water is treated with reverse osmosis and ion exchange, resulting in pure water that exceeds government drinking standards.

Professor Xia says that the methods he uses are cheap compared to other water extraction processes, and he can set up a 10,000L per day plant at a cost of less than $14,000 – incredibly cost-effective compared to other methods such as desalination. With water supplies dwindling in China and many other countries, it’s only a matter of time.