Waterproofing rules

Waterproofing mistakes are arguably the most costly to everyone. Jerry Tyrrell translates the National Construction Code (Building Code of Australia) into plumber speak.

Back in 2005, one of the first articles I wrote for Building Connection (sister publication) was on waterproofing. This time I don’t intend to:

- Refer to the 120 plus pages of information in the National Construction Code (NCC) and associated Australian Standards.

- Discuss different membranes or examine the many different forms of the same detail. The bottom line everyone wants is that “moisture does not penetrate or damage the waterproof system and the system will continue to perform for a minimum 50 years unless exposed to sunlight or a catastrophic event such as cyclone, earthquake or vandalism.” Let’s apply the same principles and rules consistently. For instance, the 150mm turnup inside a shower is the same as turnup on your balcony. A bond breaker remains the same at ANY corner. Detailing over a joint between different substrates is the same whether you are inside a drained laundry or on a roof terrace.

The source documents

- National Construction Code Volume 1 (pages 79-80 and 316-322).

- National Construction Code Volume 2 (pages 59-61 and 345-351).

- Australian Standard 3740-2010 – Waterproofing of wet areas within residential buildings (38 pages).

- Australian Standard 4654.1-2012 Waterproofing membrane systems for exterior use – above ground level Part 1: Materials (18 pages).

- Australian Standard 4654.2-2009 Waterproofing membrane systems for exterior use – above ground level Part 2: Design and installation (32 pages).

Common sense

The basic RULES of waterproofing are common sense. The way to build a dry building relies on your understanding and management of:

- Risk

- Gravity

- Material science

- Quality assurance

Risk

Risk is about identifying weather exposure, the flood height of each area, movement (especially shrinkage and between different substrates), design issues (especially complicated joints or details), specific requirements of the manufacturer, any incompatible materials and use of best practice processes and products. High risk work such as posts/antennae or thresholds fixed through membrane, suspended pools, or ground level above internal levels needs to be properly detailed with input from all stakeholders, i.e. the designer, builder, subcontractor and manufacturer.

Gravity

Grade everything – substrate and finishes – to drains. Lap and joint materials so moisture drains downhill. Fit overflows to any external area where flooding can occur.

Material science

Forget water resistant – always use waterproof membranes. Science has answers for most things. It tells us if a substance is unaffected if it is immersed in water. It tells us if a sealant is compatible with a liquid membrane. It tells us what depth and size of gravel to use to ballast a roof membrane. Most of the science is provided by the manufacturers.

Our job is to use this science to install a system where all the ingredients connect and blend without problems.

Quality assurance (QA)

QA starts with your analysis of the contract documents. Is there anything that won’t work or will be very difficult to do? If there is, fix it by issuing an RFI setting out your concerns in writing. Then you need to:

- Choose the correct waterproofing system.

- Ensure strict conformity with best practice.

- Manufacturer’s instructions, especially substrate, warnings, sequence and curing.

- All trades must respect and protect the system.

- Witness/inspection points are usually substrate, corner/joint detailing, after each coat and protection/barriers should be in place until finishes are completed.

- Ensure all finishes are compatible.

- Obtain warranties and certification

Getting started (or what I think they all mean)

I think the NCC and Australian Standards don’t intend to confuse us. So I will clarify a few things and try to translate their objectives.

As I see it, moisture is either water, water vapour or ice. Waterproof means moisture cannot travel through a substance or damage it. Water resistant means moisture cannot damage it.

The aim of the regulations is to tell us how to keep areas where moisture is present separate from other areas by what are really ‘tanks’ or impervious barriers called ‘membranes’ that permit moisture to drain, dry or do no harm.

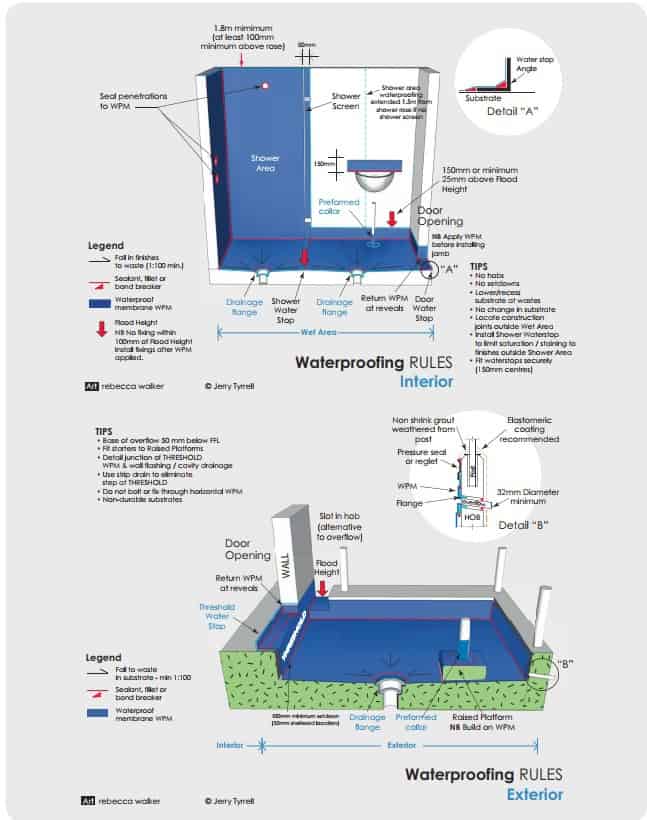

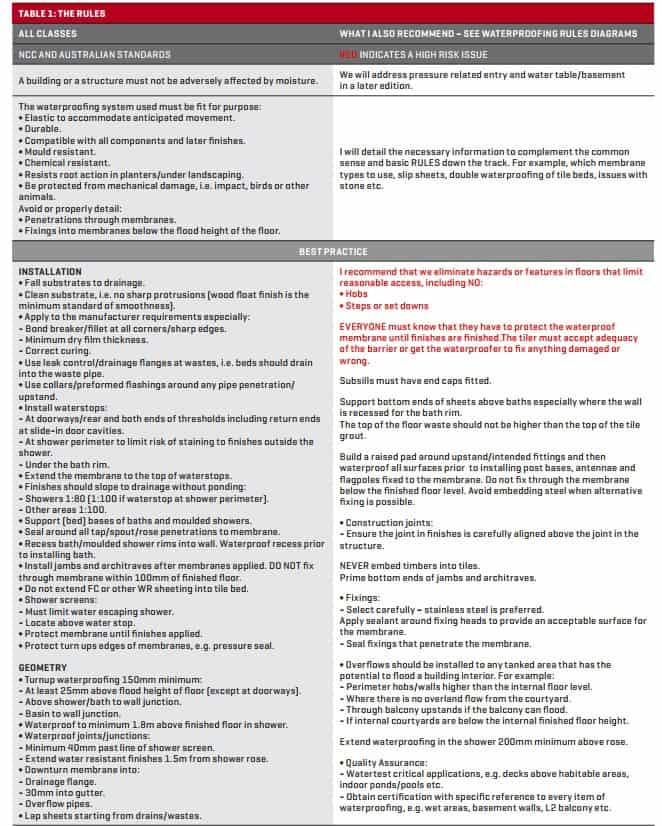

Table 1 should remind you of what you already know. Part 2 of this article will provide added detail in the next edition. (N.B: I have drawn a line in the sand and condemned some of the silly practices that have and will continue to injure occupants or cause unnecessary call backs and repair costs.)

Step 1: Understand the rules.

Refer to Table 1 – The Rules.

Step 2: Select appropriate methods/materials for the risk.

In my opinion, all products should last 50 years subject to proper maintenance (the Australian Building Codes Board agrees in its publication Durability in Buildings).

Step 3: Identify high risk issues and follow the rules.

For instance, joints between the stud wall and brickwork or weather exposed thresholds. Do not build a designer’s, architect’s, engineer’s or client’s mistake.

Step 4: Quality assure all high risk issues.

There is no substitute to inspection and testing of something which can incur $100,000 in legal and repair costs once all finishes are complete. I like to water test storm exposed thresholds before internal floors are laid.

Step 5: Get the certification.

Also check that this is supported by the manufacturer in case the subcontractor is not around in three years’ time.