UniMelb research shows improvements in construction suicide rates

Research from the University of Melbourne, commissioned by MATES in Construction, highlights that the gap in suicide rates between construction workers and other Australians is closing.

The report confirms that male construction workers die by suicide at nearly double the rate of other employed men (25.7 per 100,000 vs 14.3 per 100,000). However, in Queensland, Victoria and South Australia, rates are steadily declining and intersecting with the national average.

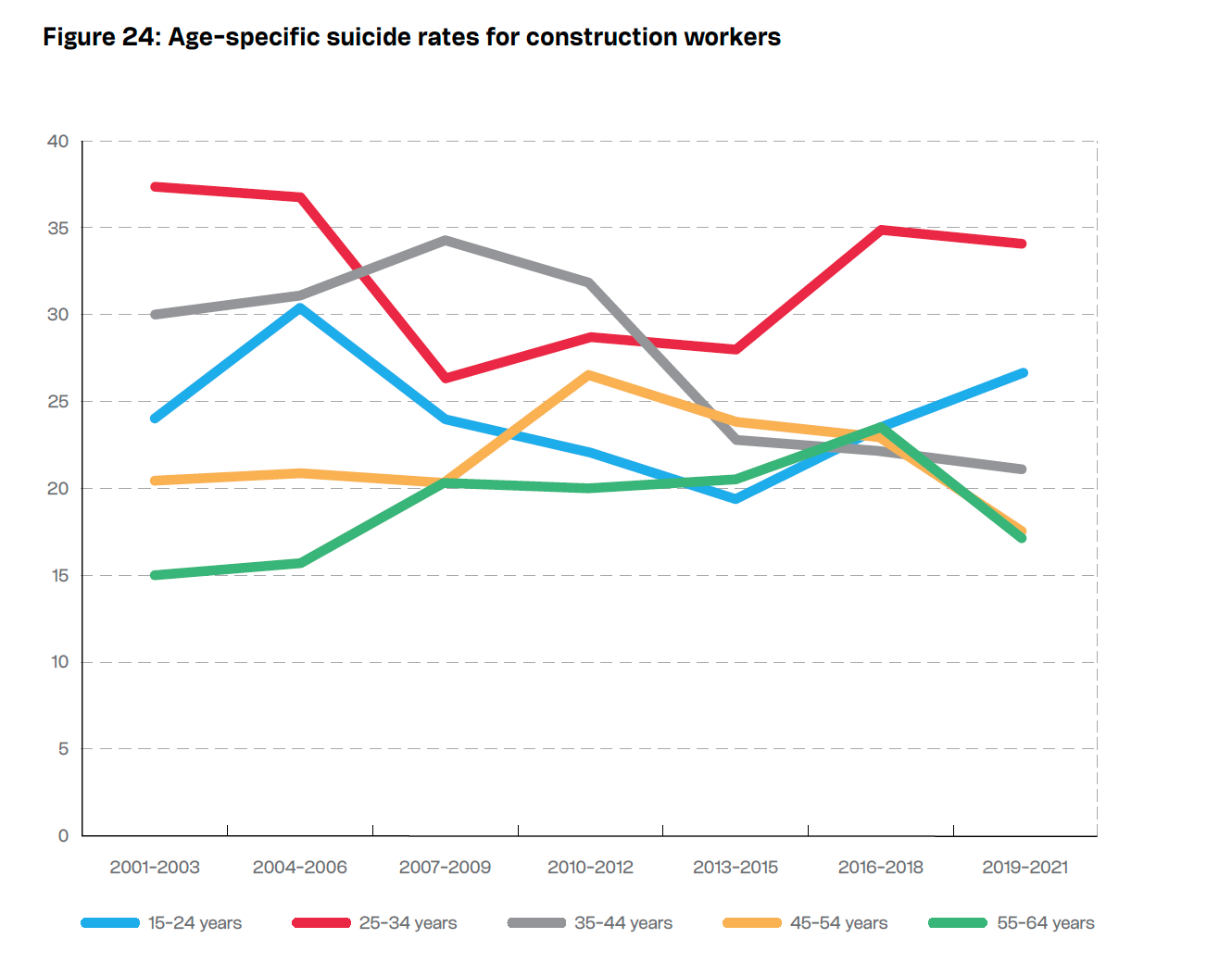

The Suicide in the Construction Industry, Volume 7, report also reveals that suicide rates among younger construction workers (aged 15-24) have been rising, contradicting the overall decline. Suicide remains the leading cause of death among Australians aged 15-24 and 25-44 with construction workers in these age groups at a heightened risk.

“While suicide in the construction industry remains higher than many other sectors, this analysis suggests that trends are heading in the right direction,” associate professor Tania King says.

“It’s important that prevention efforts build on this and continue to address suicide in the construction sector.”

MATES Australia chief executive Jorgen Gullestrup says that while any suicide is one too many, the data gives us reason for hope, but also for urgency.

“We’re seeing strong progress overall, but the increase in suicides among our youngest workers is deeply concerning. It shows we must double down on prevention and support for apprentices and younger men entering the industry,” he says.

Between 2001 and 2021, there were more than 4,500 suicides recorded among construction workers in Australia. There are promising signs with some states seeing construction suicide rates take a significant drop and others reaching parity with other industries.

This shift is supported by new qualitative research from SSM – Qualitive Research in Health that found that the MATES “network of safety” model has transitioned the social norms on worksites. Workers reported that suicide prevention is now embedded in daily workplace culture, with help-offering and help-seeking viewed as strengths rather than weaknesses.

“Construction has gone from a culture where talking about mental health was frowned upon, to one where looking out for your mates is part of the job,” Jorgen says.

“This is proof that cultural change is possible, and it saves lives.”